The Householder’s Weapon: Notes on Non-Renunciation Across the Subcontinent

But we can only accept them if we stop pretending we exist in isolation. If we acknowledge that the subcontinent has been having this conversation for millennia.

There’s a pattern hidden in plain sight across South Asian philosophy. We don’t talk about it much in Sikh discourse. Perhaps because acknowledging it feels like admitting we’re not as unique as we thought. But the pattern is there, and it’s beautiful.

The Khalsa ideal of armed householders living in the world while pursuing liberation isn’t an isolated innovation. It’s part of a deeper current running through the Indian subcontinent’s philosophical traditions, one that consistently refuses the path of renunciation.

The Gita’s Householder Revolution

Starting with the Bhagavad Gita. When Arjuna stands on the battlefield, paralyzed by moral confusion, he considers renunciation. He tells Krishna he wants to drop his weapons, retire to the forest, become a wandering ascetic. Krishna’s response is unequivocal:

BG 3.4: Not by merely abstaining from work can one achieve freedom from reaction, nor by renunciation alone can one attain perfection.

BG 3.5: Everyone is forced to act helplessly according to the qualities he has acquired from the modes of material nature; therefore no one can refrain from doing something, not even for a moment.

BG 3.7: On the other hand, if a sincere person tries to control the active senses by the mind and begins karma-yoga [in Kṛṣṇa consciousness] without attachment, he is by far superior.

This is karma yoga: the path of the householder. Not withdrawal from the world, but disciplined engagement with it. The Gita explicitly states that this path is not inferior to renunciation (sannyasa). In fact, Krishna argues that karma yoga, when performed without attachment to results, is the highest path for most practitioners.

The Himalayan Institute’s commentary makes this clear: “Karma yoga is apparent in acts of seva, selfless service... It is the spirit of karma yoga that prompts you to help with the dishes when everyone else has gone home, raise funds to carry on the work of a charity.” The mundane made sacred. The household duties transformed into spiritual practice.

This wasn’t some concession to weak-willed seekers. The traditional Hindu ashrama system explicitly included the grihastha (householder) stage as essential (not optional), not preparatory, but a necessary phase of spiritual development lasting twenty-five years. You were expected to marry, raise children, earn wealth, participate in society. Only after fulfilling these duties could one consider vanaprastha (forest dwelling) and eventually sannyasa (renunciation).

The Gita’s genius was elevating this householder stage to a complete path in itself.

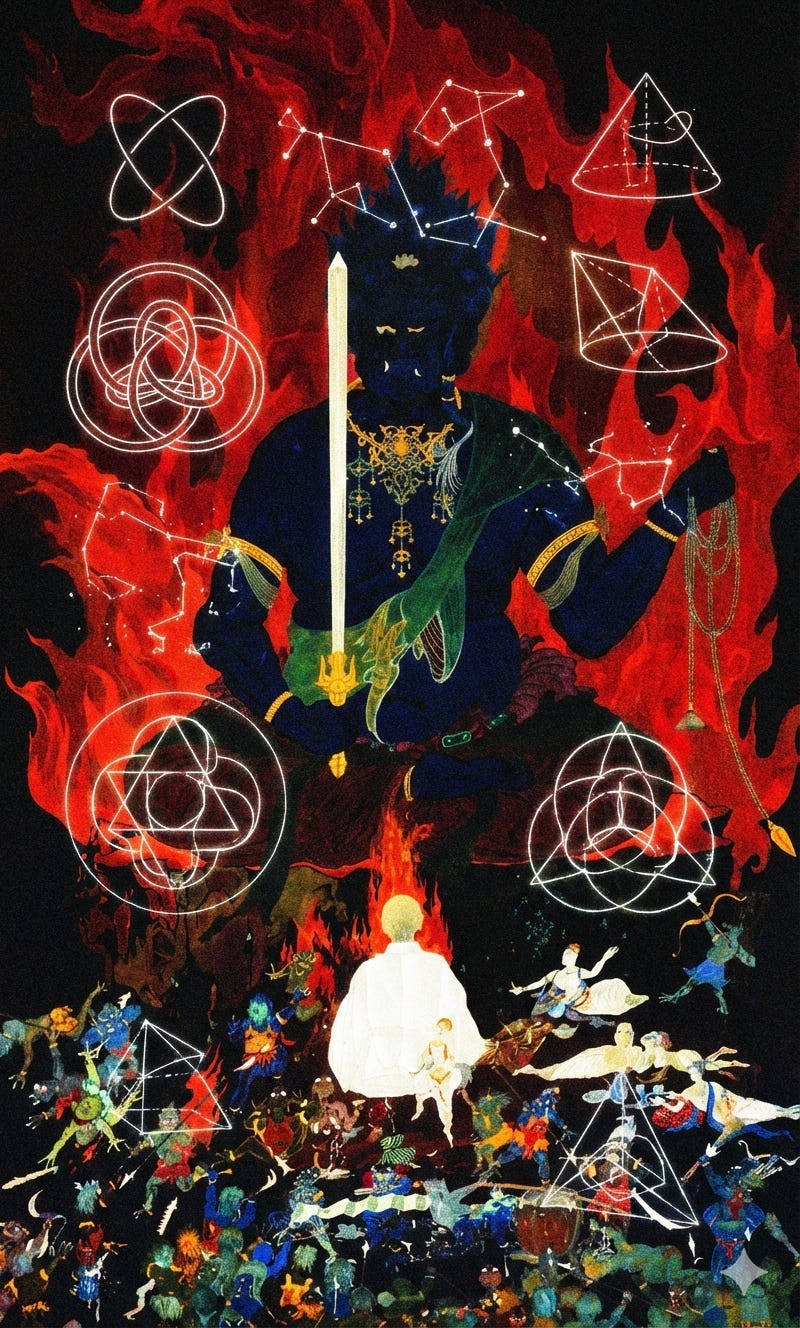

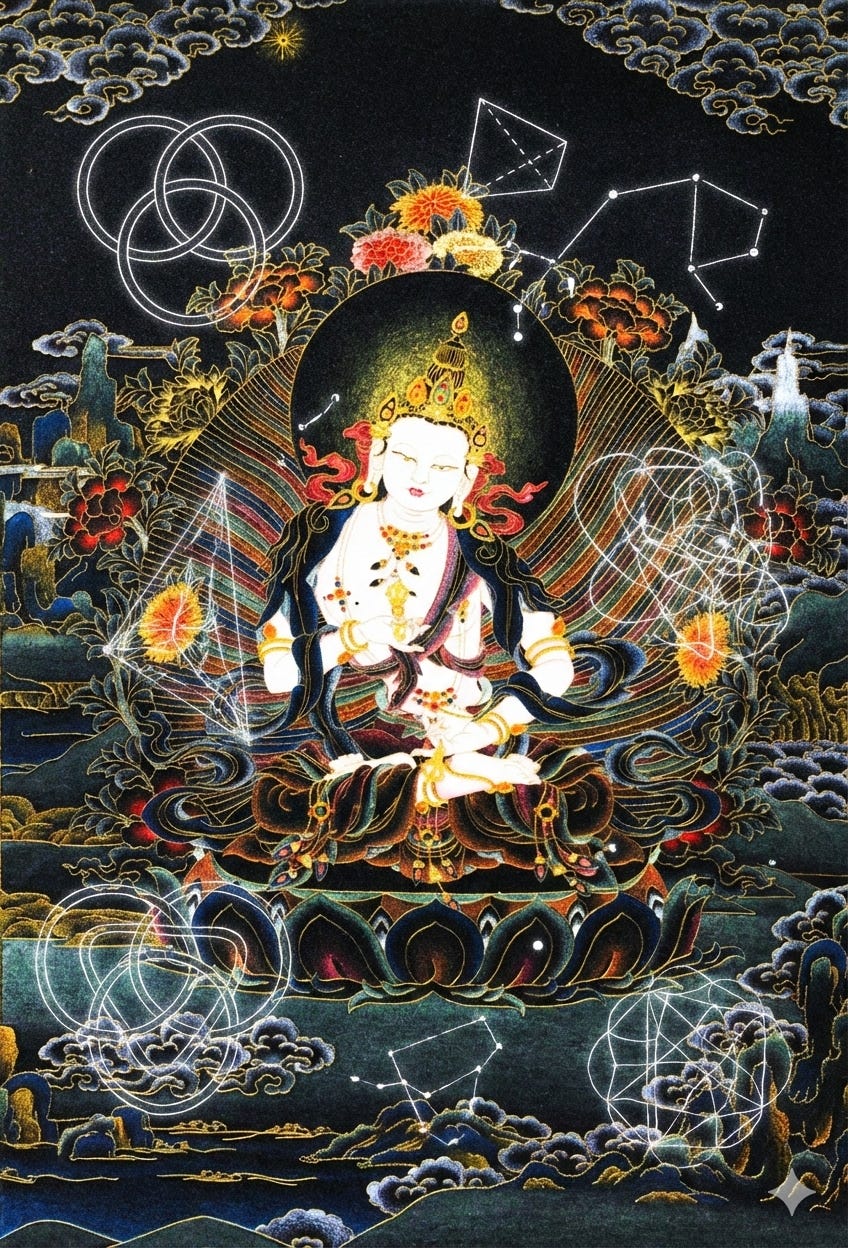

Vajrayana’s Householder Yogis: The Ngakpa Tradition

Now move north and east to Tibet. Enter the ngakpa (male) and ngakma (female): Vajrayana Buddhism’s non-monastic tantric practitioners.

Ben Joffe’s 2019 doctoral dissertation, “White Robes, Matted Hair: Tibetan Tantric Householders,” provides the most comprehensive ethnographic study of this tradition. He defines ngakpas as “Tibetan Buddhist non-monastic, non-celibate tantric yogis and yoginis” who occupy “a shifting, third space between monastic renunciation and worldly attachments.”

The key distinction: “Like monks, ngakpa are professional Buddhist renouncers, individuals who have taken formal vows to devote their lives to religious attainment and liberation. Unlike monks, however, ngakpa are non-celibate and can engage in activities forbidden to the monastics” (Joffe, 2019).

These aren’t casual practitioners. Ngakpas “spend much of their time in retreat or employed as ritual specialists for hire,” performing advanced tantric practices including deity yoga, subtle body work, and Dzogchen meditation. All while simultaneously maintaining families, owning property, and pursuing worldly occupations.

The historical precedent is significant. As the Raffaello Palandri research notes: “Padmasambhava himself, the seminal figure in the transmission of Vajrayana to Tibet, was not a monk, and many of his closest disciples were householders who attained profound realisation through tantric practices integrated into their daily lives.”

This wasn’t a concession to weaker practitioners. The ngakpa communities of Amdo and Rebkong, for example, “can rival with large monastic institutions” in terms of religious authority and ritual expertise (Lhamo, 2022). Some tantric texts explicitly argue that ngakpas hold a higher status than celibate monastics precisely because they integrate practice into the complexity of worldly life.

The tradition continues today. Chris Cordry’s ethnographic work notes: “Tantrists sometimes argue that with all its complexity and difficulty, the householder life provides even greater opportunity for awakening than a monastic one. After all, monks don’t have to navigate the challenges of long-term romantic relationships, pay taxes, or raise kids.”

And yes, historically, ngakpa communities consumed meat and alcohol in specific ritual contexts (ganachakra feasts), wore distinctive white robes and matted hair, and performed “subjugating activities” that included ritual uses of weapons and symbolic “liberation” of enemies.

Armed householders pursuing the highest realizations. Sound familiar?

Kashmir Shaivism: Be in the World, Enjoying It

Now to Kashmir. The Shaiva philosophers of medieval Kashmir—particularly Abhinavagupta (10th-11th century)—developed what might be the most explicitly anti-renunciate system in classical Indian philosophy.

The Shehjar magazine’s article on Kashmir Shaivism puts it directly: “The life of utter renunciation is not incompatible with worldly life that has its own place in the scheme of things... Not approving any form of forcible repression of the senses and the mind, it has developed methods that could be followed equally by both the monks and the householders.”

Dr. Navjivan Rastogi, former Director of the Abhinavagupta Institute of Aesthetics, states: “Kashmir Shaivism is not rooted in sorrow, nor does it look to liberation (moksha) as a way out... While recognizing worldly enjoyment as a goal of life, it does plead for a spiritual path aimed at harmonizing worldly enjoyment (bhukti) and the desire for liberation (mukti).”

This is radical. Most Indian philosophical systems treat bhukti (enjoyment) and mukti (liberation) as opposed. You either pursue one or the other. Kashmir Shaivism says: why not both?

The tradition “abhors the torture of the body or mind, does not plead for suppression or forced control but lays stress on sublimation and gradual turning away from the lure of wealth, power and sense pleasures.” Notice: gradual. Not immediate renunciation. Not forcible control. Sublimation while remaining engaged.

Abhinavagupta himself “shattered the established belief that laid emphasis on caste, creed, color and gender restrictions in relation to spiritual practice... He abhorred the idea that spiritual revelation was only possible in purely monastic surroundings. He refuted that those caught in the householder way of life had to wait“ (abhinavagupta.org).

The Vijnanabhairava Tantra, a core Kashmir Shaivism text, contains this stunning verse:

“Listen: Neither renounce nor possess anything, share in the joy of the total Reality and be as you are!”

Don’t renounce. Don’t grasp. Just be.

And yes, they ate meat. Swami Lakshman Joo, the 20th-century Kashmir Shaivism master, spent considerable energy arguing against meat-eating. But even he had to acknowledge “the ancient śāstras, particularly those of Kashmir Shaivism, ordain meat-eating.” Specifically, in the context of certain initiations (dīkṣā) performed by realized masters, meat consumption was not only permitted but prescribed as part of tantric ritual transformation.

The Pattern: Ritual Meat, Weapons, Worldliness

Let me pause and gather the threads:

Bhagavad Gita: Householder path (karma yoga) as supreme. Engagement with the world, including warfare, as spiritual practice.

Vajrayana (Ngakpa tradition): Householder yogis who marry, own property, eat meat and drink alcohol in ganachakra rituals, carry ritual weapons, perform “liberations” (ritual killings of enemies/demons). (Note: I am not advocating for any mind-altering substance being used.)

Kashmir Shaivism: Explicit rejection of renunciation. Harmonization of worldly enjoyment and liberation. Historical meat consumption in tantric initiatory contexts.

Now add Sikhi to this list:

Sikh tradition: Householder path (grihast sansar) as ideal. The Sant-Sipahi (saint-soldier). The Khalsa as armed community. The Miri-Piri doctrine (temporal and spiritual authority unified). Explicit permission for Jhatka meat consumption. Rejection of asceticism in the Adi Granth:

ਸਤਿਗੁਰ ਕੀ ਐਸੀ ਵਡਿਆਈ ॥

ਪੁਤ੍ਰ ਕਲਤ੍ਰ ਵਿਚੇ ਗਤਿ ਪਾਈ ॥੨॥Satigur kee aisee vadiaaee.

Putr kalatar viche gat paaee. ||2||Such is the Glory of the True Guru;

Salvation is attained even in the midst of children and spouse.

Adi Granth (Page 661)

The parallels aren’t superficial. They’re structural.

The Broader Outlook

I’m not arguing Sikhi is “derivative.” Clearly, these traditions developed in different times, places, and contexts. The Gita emerged in the context of Brahminical debates around 2nd century BCE-2nd century CE. Vajrayana developed across centuries in India and Tibet. Kashmir Shaivism flourished in the 9th-12th centuries. Sikhi crystallized in the 15th-17th centuries Panjab.

What I am saying is this: the householder path as a legitimate, even superior, route to liberation is a recurring philosophical stance across the Indian subcontinent.

It’s not unique to Sikhi. It’s part of a deeper Indic counter-tradition to the renunciate ideal that dominated so much of classical Indian philosophy (Buddhism’s sangha, Jainism’s munis, Vedantic sannyasis).

This counter-tradition says:

You don’t need to abandon the world

Marriage and family aren’t obstacles

Wealth earned ethically isn’t bondage

The body isn’t something to torture

Meat consumption isn’t inherently polluting

Weapons in righteous hands serve dharma

Worldly engagement can be spiritual practice

Sikhi inherits this counter-tradition. It systematizes it. In some ways with the Khalsa institution and the doctrine of Miri-Piri—it perfects it. But it doesn’t invent it from nothing.

The Subcontinent’s Gift

Here’s what I think: recognizing these parallels doesn’t diminish Sikhi. It enriches it.

It situates our tradition within a profound philosophical conversation that spans centuries and regions. It shows that the Gurus weren’t isolated innovators but participants in a living debate about how to pursue liberation.

It demonstrates that the questions Guru Nanak asked—How do we live spiritually in the world? Must we renounce to be free? Can the householder attain mukti?—were questions others were asking too.

And it suggests that if we want to deepen our understanding of Sikh philosophy, we might learn from studying these parallel traditions. What does Abhinavagupta’s analysis of aesthetic experience (rasa) tell us about Gurbani’s use of ras? How do Vajrayana teachings on the subtle body illuminate the SGGS’s references to dasam duar and trikuti? What can karma yoga’s emphasis on detached action teach us about seva?

These aren’t threats to Sikh uniqueness. They’re invitations to intellectual depth.

But we can only accept them if we stop pretending we exist in isolation. If we acknowledge that the subcontinent has been having this conversation for millennia. And that the Gurus’ genius wasn’t inventing the householder path. Rather, it was embodying it with such clarity and institutional force that it created a people.

That’s the real achievement. Not uniqueness. Realization.

Further reading: Bhagavad Gita (any translation); David Gordon White, “Sinister Yogis” (on tantric traditions); Alexis Sanderson’s work on Kashmir Shaivism; Geoffrey Samuel, “Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Tibetan Societies” (on ngakpa communities).